soundtrack series: dog days are (never) over

the ethereal, enduring appeal of Florence and her machine, and her lasting influence on millennial women choosing to step into their own power

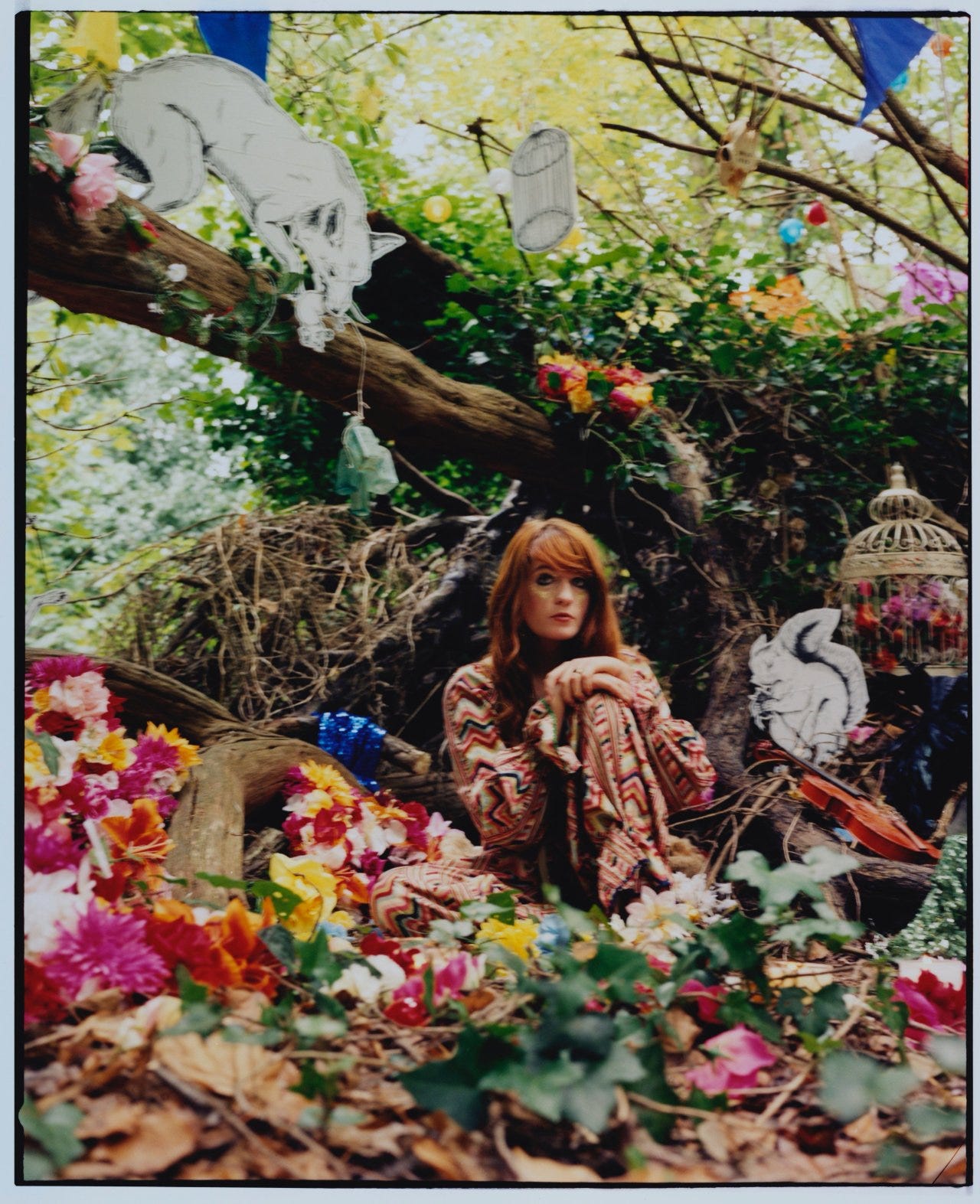

A lone figure walks out to the middle of the stage, her pale face upturned to the spotlight. She is wearing a short, sequinned dress and a ruff of feathers, iridescent blue and green, that contrast with the deep russet of her long, wavy hair. The crowd is restless and chatting, disinterested in paying attention to the opening act of a four band lineup - until she opens her mouth. It is the 21st February 2009, and Florence Welch has just filled Brixton Academy with song.

On that night, in that moment, sitting in the front row of the circle, my entire nervous system woke up. I sat forward, leaning towards the stage, and the rest of the room faded away. A quiet fell over the rest of the crowd as everyone’s attention was fixed on Florence and her voice - that voice - that echoed and soared through the hall of Brixton Academy, a room already haunted by decades of musical history. This powerful opening morphed into a clattering, dramatic full band performance, with handfuls of glitter spraying from drumheads and Florence hurling her limbs around the stage for the entire show, seemingly possessed (in hindsight, possibly quite drunk). Everyone in the room knew that we were witnessing something special; a performance that would be added to the venue’s iconic lore.

That was my first time seeing Florence; she was part of the NME Tour, alongside White Lies, Friendly Fires, Glasvegas. Given the amount of buzz surrounding her at the time, it would have been hard for me not to have heard about her, and her mythology; the oft-referenced fact that she convinced Mairead Nash to manage her by singing ‘Something’s Got a Hold of Me’ by Etta James in a pub toilet, her vaguely posh family, her classical training, her hair. She was electric.

Florence had begun to appear in the pages of every hipster publication and at many of the vaguely fashiony, internet culture events I was attending; except she was special, because she was actually doing it: making art in a sea of others who were just pretending to. A true poet with Pre-Raphaelite sensibilities and the ability to cut out her heart for a chorus, using the still-beating blood to write the narrative of every love affair gone wrong. Florence personified the post nu-rave, pre-Tumblr sensibility, a weird mashup of Zoe Deschanel twee, futuristic Scandi popstar, and early 1900s cabaret icon, all sparkles and velvet and bows and weird wedge platforms that she never looked comfortable in. Just like the rest of us, really. As the cult of Lungs swept through the land, you couldn’t escape the opening harp of ‘Dog Days Are Over’, twinkling through every Channel 4 teen drama montage. For those of us who were already hooked, seeing her live cemented the fact that we had a once in a generation artist on our hands; still reeling from the death of Amy Winehouse, hers was the voice that now spoke to the Myspace girls who might have stripped the black dye out of their hair, but still had too many feelings and nowhere to put them. Being at fashion school at the time Florence emerged from her chrysalis, she quickly became a perpetual touchpoint whenever we were searching for inspiration. There was always something vaguely unhinged about her, but we connected with that, too. In an extremely of-the-era move, I nearly got the maddeningly romantic lyrics for the chorus to ‘Cosmic Love’ tattooed on my thigh, back when I thought that song was what love should feel like. I’m thankful now that it’s a little too wordy to make a good tattoo.

Her cover of ‘You’ve Got The Love’ brought her further into the consciousness of the general public, but my parents couldn’t yet understand the appeal of the ‘screechy, squawky’ girl I was newly obsessed with. They watched her performance at Reading Festival 2009 on the TV with me, my mum holding her hand over her mouth in concern as Flo scrambled up the rigging in heels, her feet slipping with every step. They were flummoxed. I was entranced. Florence had the same energy as Amy; a uniquely glamorous, angrily defiant icon, singing about her greatest pain with her entire chest.

With the release of Ceremonials, which I consider to be her most spectacular album (albeit too intense for frequent rotation) she demonstrated the first signs of the complete artist she was evolving into. Her songs were operatic in scale, her performances regal and her vision cohesive. Not many other popstars of that era were referencing Virginia Woolf and Tamara de Lempicka in their work; Florence’s 1930s, Art Deco image for this album took the zeitgeist’s enthusiasm for a vintage aesthetic to its apex. She started working with Karl Lagerfeld, who took the photographs for the album cover, and performed at the Chanel catwalk show as Bottecelli’s Venus, emerging from an oyster shell encrusted with pearls. It was the stuff of our Lula magazine, Sofia Coppola fantasies and it felt fitting to witness the tour for this record at Alexandra Palace, a suitably cathedral-esque setting.

By this point in my career I was working as a fashion journalist, and left my parent’s house in Sussex at 5.30am on Boxing Day, 2011 to travel to Harrods, where Florence was officially ‘opening’ the sale. The air was frosty as I stood outside the department store in the roped-off press pen next to some gruff paparazzi, drinking bitter coffee and waiting for the event to start. A small crowd of fans and bargain hunters waited by the barriers outside the store entrance, eager to get inside. At the stroke of 9.30am, a lantern-lit carriage pulled by horses wearing grey feather plumes rolled up outside the building. Florence stepped out like a ghostly vision in a dove grey cape, taking to a small stage to sing an acoustic version of ‘What The Water Gave Me’. After her performance I was swept up to the VIP personal shopping area in the penthouse - a black marble, footballer’s wives paradise. The thickly carpeted room we’d been assigned for the interview had a coffee table covered in copies of the latest VOGUE, which featured Florence on the cover. Walking in, she immediately turned the one nearest her over, saying “I can’t possibly do this with that looking at me” and laughed that the Chanel couture she was wearing had made her realise that she was allergic to wool. It is exactly this balance of unabashed earnestness and self deprecation that makes her relatable, even when everything else about her isn’t. She was shy and tired, telling me that she’d decided that she was dressed as long as she was wearing jewellery, so she’d spent Christmas Day in costume jewels and pyjamas. Her energy was erratic, her voice soft and quiet, until she had to shriek for her sister/assistant Grace’s input on a question, or when she burst into a cackle of laughter. I realise now that I was meeting her potentially at the beginning of her sobriety. By this point, my mum and dad had warmed to Flo and were suitably impressed by her star quality; when I got back to the house in time for a plate of leftovers and the last of the Christmas TV, we listened back to the audio recording of our interview.

Few artists apart from Amy have so accurately captured the drunken, messy, yet hopeful adventures of the generation that came of age in the Noughties (a word that people seem to have stopped using since the wave of Y2K nostalgia first reared its ugly head). However, Florence has managed to successfully transfer her creative genius from the melodramatic chaos that soundtracked us snogging the wrong people and staying up all night to the powerfully reflective hymns of self-awareness that made her last three albums transcendent.

This process began on How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful, an album steeped in the raw emotion and 70s mystique that has come to define Florence’s work. Written between the Chelsea Hotel and the Chateau Marmont, Flo began to reveal the quieter counterpart to her otherwise whirlwind energy; just like her peers, she began to grow up. When that album was released, I was in the grip of an obsessive love and floating in the aftershock of a nervous breakdown, still addicted to the supernova energy of her previous records; in contrast, HBHBHB almost felt too refined, too real. Her work had reached a greater poetic realm, and with hindsight, it is apparent that being newly sober was bringing her the accelerated clarity of a woman who knows exactly who she is. As someone listening who still had a long way to go on that journey, there was something unsettling about the album, like it was scrying a future I didn’t want to know about, one where love didn’t, in fact, save us. Instead, I latched on to the idea of ‘St Jude’ and his lost causes. I didn’t know then that eight years later, I’d be an entirely different (healthier, happier, also sober) person, walking along the Brighton seafront at sunrise, listening to Florence’s 2023 single, ‘Mermaids’ and feeling like I’d been punched in the chest with nostalgia. That song, which references the debauchery that Brighton does best, somehow manages to capture the essence of Florence’s early music, the unravelled madness that drew me to it in the first place, whilst combining it with the wisdom and grace she has acquired with age. Listening to it reanimates the fuck-it-do-it-for-the-story version of me that would have been doing shots in a grimy venue at 3am and kissing someone I didn’t like, waking up hating myself the next day. It is bittersweet and beautiful, a mirror into the past that deserves to remain broken.

High as Hope, the album released in 2018, brought with it a vulnerability that both spoke to the movement of the times and brought her fanbase closer than ever. Using her first single, ‘June’ to address the eating disorder that she’d never before spoken about (with anyone), was a braver move than even her most avid fans would have expected. For a generation who had been raised to hate our appearance, it was both validating and inspiring to watch one of our own transform the hellish experience of disordered eating into art that subsequently became an international hit. Florence began to open up on other levels, releasing a book of poetry and writing frankly about addiction, mental health and eating disorder recovery in an essay for Vogue. One line from that essay burned itself into my brain: writing about the too-familiar desire to punish our bodies, Florence tells us to work with them, not against them, and that ‘you do not beat your own heart’. As a person who has spent the majority of my life feeling like a floating head in a permanent state of dissociation, thanks to eating disorders and sexual violence, I have never needed to hear something quite so much.

On a physical level, I am grateful to exist as a woman at the same time that a broad swathe of artists at the forefront of the industry are presenting themselves as themselves, inverting decades of popstar norms. Aside from their stage outfits, Florence, Boy Genius and Haim are just a handful of the performers you are just as likely to see in outfits that look a lot like what other women their age wear. It’s also semi-normal now to see them without makeup that masks their natural features; long gone are the lids laden in glitter, bone white face and blood red lips of her early career, in favour of make-up that barely looks like make-up at all. She looks more beautiful than ever, but most importantly, she looks like herself. Writing this has sent me on many tangents about how I perceive myself, and how much more comfortable I am in my own (bare) skin now than I ever used to be. Whilst this is mostly thanks to a combination of therapy, reading and deprogramming, seeing women I admire achieve their goals without feeling the need for a red power lip has definitely encouraged me to leave my lipstick in the drawer. I think I’ve worn it less than a handful of times this year, and every time now feels a little bit off. It does not imbue the sense of false confidence in me that it used to; instead I resent the distraction that it creates from my own concentration and those who I want to listen to me. Watching Florence’s early music videos back, I’m struck by how overdone and awkward she looks, in comparison to the godly confidence she now embodies.

The rejection of performative femininity and the unnecessary pressures of womanhood are threads that run through Dance Fever, Florence’s latest album. In a conversation with Zane Lowe upon its release, she discussed the meaning behind its first single, ‘King’, explaining how she had reached what she considers to be the pinnacle (thus far) of her performing and songwriting abilities, just as she is also reaching the age when the expectations of marriage, children, and anti-aging kick in at their maximum force. In comparison to male performers at the same age, who could start a family without it impacting their professional trajectory, the same is not true for her, and she was faced with the crossroads decision of running towards her power or taking a detour down a more conventional route. Whether or not Florence ultimately chooses to have a family will not detract from her artistic talent, but it’s an unavoidable fact that it could impact her ability to rise up through the ranks of legends at the same volition. There’s a reason why Stevie Nicks never had children, and I believe the world is better off as a result. As I also emerge now at the most fully formed version of myself, childfree and confident in the fulfilment I get from my own work, Florence is singing for those of us who have chosen to live outside what is expected of and from us as women, as people. She has been bold enough to declare that she will not be subdued: she is forging a formidable legacy and is unprepared to quiet her greatness. She is no mother, she is no bride, she is king.

[photos by Tom Beard and Autumn de Wilde respectively]